Wildfires spark muirburn debate

Recent wildfires have reignited debate about muirburn and wildfire risk in Scotland’s warming climate. But the contested merits of muirburn mask deeper divides over whether and how we want our landscapes to change, and what functions we need Scotland’s natural environment to serve.

Part of our ‘The Big Picture in Focus’ series, providing a deep dive into the stories that impact Scotland’s road to nature recovery.

When two separate wildfires near Carrbridge and Dava became one in late June 2025, they formed Scotland’s largest ever wildfire, eclipsing the previous record set at Cannich just two years previously. The growing impact of wildfires in Scotland’s warming climate has reignited debate around muirburn and our preparedness for this rising threat, yet the real argument isn’t about muirburn, or even wildfire risk, but something much more fundamental.

Muirburn has taken place for centuries but was closely regulated by landowners until the 20th century. In 1784, the Freeholders and Justices of Peace of Sutherland let it be known that they were ‘determined to prosecute with the utmost Rigor of Law all such as can be discovered burning Muirs in forbidden times.’ The forbidden period then ran from 1 March to 20 September – arguably more appropriate dates than modern rules which, until 2026, allowed burning from 1 October through to 15 April, or even later.

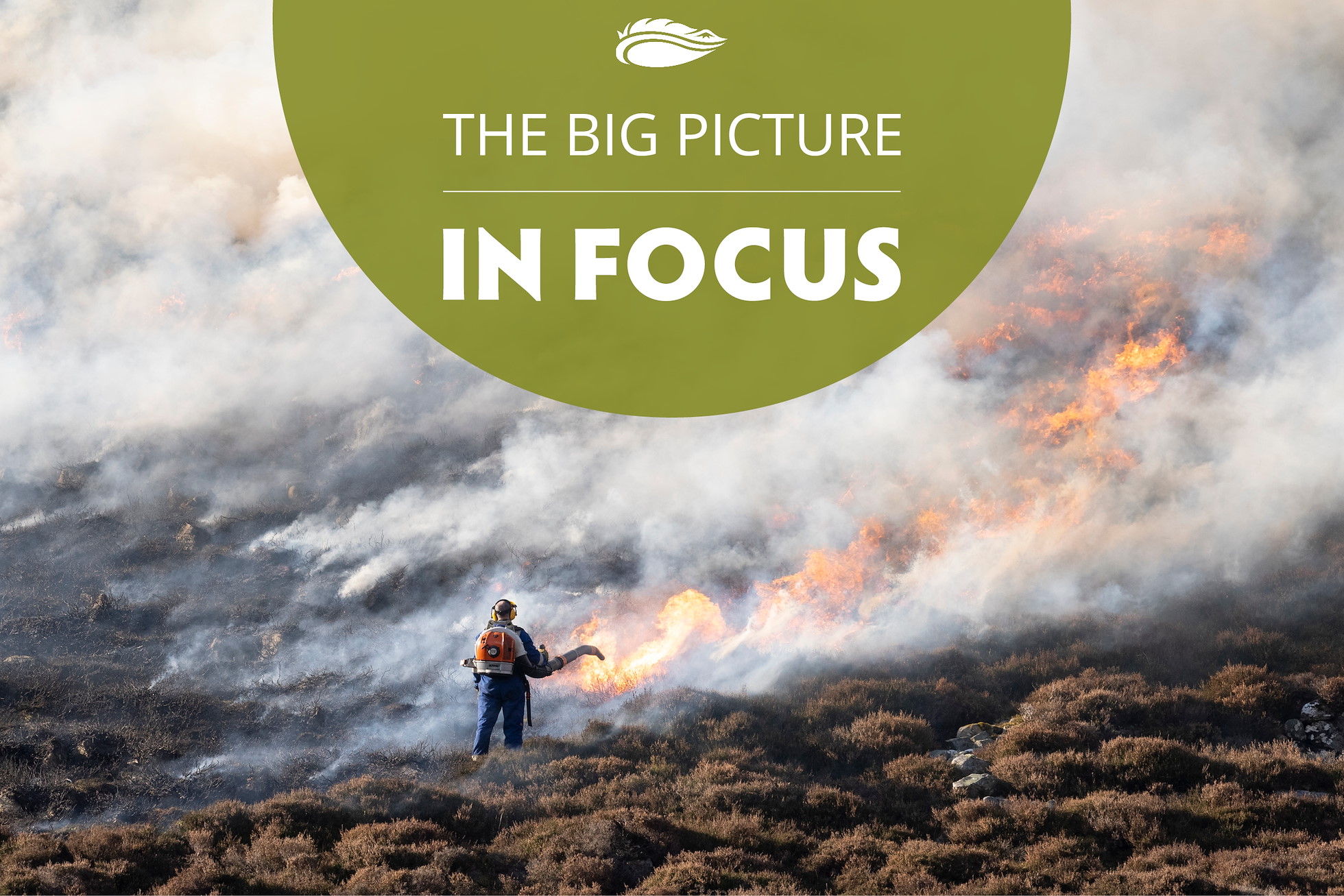

Muirburn involves setting fire to heather or grassland in moorland habitats. Usually, these controlled burns are designed to encourage fresh vegetation growth, creating favourable conditions for red grouse or improve grazing for livestock. Many of those invested in traditional land management therefore value muirburn as a vital tool, integral to the land uses they favour. They also claim it’s important for managing the risk of wildfire. But while there is undoubtedly some truth in this claim, the full picture is much more complicated.

Fighting fire with fire

The logic of using controlled burns to reduce wildfire risk is simple: muirburn prevents the natural build up of vegetation. This means that there is less standing vegetation to fuel future fires, making wildfires less hazardous and much easier to extinguish. Fresh muirburn scars can also serve as a form of firebreak. By contrast, when wildfires occur on moorlands that have not been burned for a long time, the greater abundance of vegetation can fuel a much hotter fire.

Muirburn scars currently cover more than 5,000 km² of Scotland.

But there are other ways in which muirburn may increase the risk of wildfire. For example, over time, muirburn can increase the dominance of molinia grass and heather over blanket bog vegetation. Since heather and molinia grass can become exceptionally dry and vulnerable to ignition, especially in Spring, this may lead to a more fire-prone environment. It’s not a coincidence that the largest UK wildfires have occurred on moorlands, heathlands and grasslands.

‘Put a freshly cut log on the fire and the most you can reasonably hope for is a smokey hiss.’

So, while any build up of vegetation can increase fuel loads - and thus the risk of a really hot wildfire - the continued use of muirburn also imprisons habitats in an unnatural and potentially more fire-prone state. By contrast, so long as it remains unburned, natural vegetation growth can eventually develop into a mosaic of more fire-resistant habitats. As Oliver Rackham famously observed, most native British woodlands ‘burn like wet asbestos.’ It’s why most firewood has to be seasoned. Put a freshly cut log on the fire and the most you can reasonably hope for is a smokey hiss.

Beneath the cool, shady canopy of deciduous woodlands, damper conditions prevail, creating natural firebreaks and vital wildlife refuges which wildfires struggle to penetrate.

The one species of native tree that does burn relatively easily whilst alive is Scots pine. Scots pine almost wholly dominates forests in the cold, relatively dry east of Scotland, leaving these pinewoods vulnerable to wildfire. But pinewoods in the milder, more humid west often include stands of birch, rowan, alder, willow, holly and hazel. In these more diverse, more complex environments, sooner or later wildfires come up against natural firebreaks.

Still, even if pinewoods in the dry east may be more vulnerable to wildfire, it hardly follows that we should abandon our rewilding ambitions or the restoration of these habitats. After all, in the face of Scotland’s sad ecological impoverishment, most Scottish people are keen to see more trees. What we need instead is a richer mosaic of natural habitats in which fire spread is less rapid and more easily interrupted. Muirburn certainly won’t deliver that. It may not even always be the best way to reduce wildfire risk in moorland habitats.

A complex relationship

The fire-prone nature of the habitats created by muirburn makes the relationship between muirburn and wildfire risk complicated. Although muirburn is supposed to be controlled, managed burns can get out of control. Indeed, fire and rescue records show a significant proportion of controlled burns escape to become wildfires. So it’s hard to know whether muirburn prevents more fires than it causes.

One recent study, which mapped the spread of Scottish wildfires between 2015 and 2020, found only limited overlap between those areas affected by wildfire and those showing a visible history of muirburn. The study’s authors suggested this might be because muirburn reduces the amount of fuel available. But they also pointed out it could be due to better fire prevention efforts on managed estates, or fewer people lighting campfires or barbecues in those areas. Interestingly, the study also found that while the area affected by wildfire was generally lowest in areas of low to medium intensity muirburn, it was often higher in places of higher muirburn intensity.

‘The overwhelming proportion of moorland in the tally of burned habitats speaks to the vulnerability of the landscapes created by muirburn.’

A report by Scottish Land and Estates following the Carrbridge-Dava fire documented that it ultimately covered around 10,574 hectares of moorland and 1,253 hectares of forest. Dava Moor is used for both grouse shooting and sheep, and much of this area had previously been subjected to muirburn. Clearly muirburn didn’t prevent this massive wildfire, and while the history of muirburn here may have created some firebreaks, the overwhelming proportion of moorland in the tally of burned habitats – almost 90% – speaks to the fundamental vulnerability of the landscapes created and maintained by muirburn. This pattern thus illustrates the double-edged nature of muirburn, a tool that can help tackle fire spread but also increase vulnerability to wildfire.

Muirburn creates patches of shorter vegetation that wildfires struggle to ignite, but large wildfires simply burn around these ‘firebreaks’, spreading freely through surrounding areas of longer grass or heather until they meet more contiguous firebreaks in the damper conditions found in gullies, deciduous woodlands and bogs.

In a comprehensive review published in 2022, NatureScot concluded ‘there was a lack of evidence relating to muirburn controlling the extent of wildfire in moorland.’ Amidst this uncertainty, muirburn seems to have two main benefits, both linked to the way it reduces fuel loads: 1) it helps keep moorlands in a condition where wildfires are easier to tackle and 2) it may make moorland wildfires less damaging. On the other hand, muirburn is undoubtedly responsible for starting some wildfires, and it also creates and maintains landscapes that are more susceptible to catching fire than most natural habitats.

Wider impacts

Away from arguments about fire risk, muirburn is sometimes claimed to benefit threatened species like curlews. But any such benefit comes at a cost to other forms of native wildlife that can be negatively impacted by fire, particularly reptiles, amphibians and invertebrates. In any case, curlews are more likely to benefit from the predator control conducted in these same habitats than the burning itself.

Muirburn may create favourable conditions for some ground-nesting birds but it can also threaten nests. These eggs - photographed after muirburn got out of control in early April, 2025 - have been destroyed.

Meanwhile, the negative impacts on wildlife from muirburn extend even beyond the moors. A study in Northern England compared the diversity of large invertebrates across ten rivers, five draining burned catchments and five draining unburned catchments. The study showed that rivers draining burned catchments supported significantly lower taxonomic richness, with notably reduced abundance and diversity among mayflies. Upland watercourses also need the shade, nutrients and diversified flows that are provided by mature riverwoods – vital habitats that muirburn and grazing have greatly restricted.

Environmental costs

Historically, muirburn has been governed by the Muirburn Code. But various aspects of this code - including the avoidance of burning on peatlands, thin soils or steep slopes – have long been flouted. A recent study estimated that 32% of muirburn continued to take place on deep peat soils, even after the revision of national guidelines in 2017.

‘Various aspects of the Muirburn Code - including the avoidance of burning on peatlands, thin soils or steep slopes - have long been flouted.’

Peatland soils in the UK uplands are a particularly important carbon store – or at least, they should be. Thanks to their current poor state, our peatlands have flipped to being net carbon emitters, a disaster partly attributed to the inappropriate use of muirburn. In response, the Scottish Government’s Wildlife Management and Muirburn (Scotland) Act 2024 aims to ensure that muirburn and the closely associated management of grouse moors is carried out in a more 'environmentally sustainable and welfare conscious manner.’

But ensuring the environmental sustainability of muirburn remains challenging. Firstly, vegetation fires emit significant amounts of pollutants into the atmosphere, including large volumes of soot, greenhouse gases and volatile organic compounds (VOCs). Wildfires release all these pollutants too of course, and a hot fire will release more than a cool, controlled burn. So a key question is whether muirburn causes more or less pollution overall than wildfires.

Environmental concerns surrounding muirburn range from air pollution to questions about its impacts on carbon storage, peatland hydrology and flood risk, together with more profound questions about how such managed landscapes can be reconciled with Scotland’s ecosystem restoration goals.

Around 61km² of Scotland is deliberately burned each year, releasing a certain amount of pollutants. But these controlled burns may also prevent some wildfires or, failing that, stop others from becoming much larger blazes, releasing a greater amount of pollutants. So if every square inch of ground subjected to muirburn would otherwise burn in a larger wildfire, then muirburn would certainly mean a net reduction in air pollution, but this isn’t the case. And because it’s difficult to predict how much of the land subjected to muirburn might otherwise have burned in a wildfire – and because some of the land freed from muirburn may absorb more carbon in the pulse of vegetation growth allowed by an end to burning – determining whether there are any pollutant ‘savings’ from continued muirburn is almost impossible.

‘If every square inch of ground subjected to muirburn would otherwise burn in a larger wildfire, then muirburn would certainly mean a net reduction in air pollution, but this isn’t the case.’

It’s perhaps unsurprising then that NatureScot’s review found ‘no overall consensus’ concerning the net impacts of muirburn on carbon budgets, with ‘conflicting evidence supporting gains, losses and no difference in carbon stores’ following muirburn. However, it remains true that when wildfires penetrate into peat, they are especially hard to extinguish and can release significant amounts of carbon. Questions about pollutants and carbon thus depend not only on whether muirburn helps to reduce the number of wildfires, but also on whether there are alternative ways to prevent such fires – which we know there are.

Wetter is better

One commonly used approach to reducing wildfire risk in peatland habitats is mowing. Whilst not practicable everywhere, where it matches other habitat management objectives, it offers a fire-free approach to reducing fuel loads. Another option may be carefully managed grazing, although the risk with grazing animals is that overgrazing can also degrade peatland habitats. It’s a tricky balance. The best option for making vulnerable peatlands more resilient is therefore through rewetting. Blocking drainage ditches, adding dams and removing any extractive pressures helps to secure the carbon these peaty soils contain, buffering them against the risk of fire.

Rewetting can also help reduce flood risk, slowing runoff into rivers, while muirburn can have the opposite effect. After both controlled burns and wildfires, peatlands can develop water-repelling crusts and blocked microchannels, which increase surface runoff, raise streamflow peaks and cause more erosion. Trees also reduce flood risk by intercepting rainfall and helping water soak into the ground, but muirburn prevents woodland regeneration. Is flooding a greater risk, or bigger threat, than wildfires in our changing climate? It’s hard to say. But it’s worth noting that supporters of muirburn often focus more on the risks of wildfire than those of flooding.

The heart of the matter

All this complex and conflicting evidence has allowed different groups to build arguments both for and against muirburn, often drawing selectively on the available evidence to support their views. The debate also reflects the increasingly contested nature of knowledge itself, with some placing greater value on scientific research and others leaning more on lived experience. But at its heart, the disagreement comes down to deeper questions around the purpose of our landscapes: how we reconcile biodiversity restoration, food production, energy security, ecosystem services, wildfire risks and flood prevention among all the other things we need land to provide – and whether we can agree about which changes to prioritise.

In recent decades, moorlands across the UK have seen a reduction in grazing pressure. This has been due to changes in farming subsidies, the shift towards having fewer deer on the hills, and a growing focus on reforesting land and restoring peatlands. But some supporters of more traditional land uses have pushed back against these changes, spurred on by fears about threats to the status quo and a growing belief that less grazing and more vegetation leads to higher fuel loads, making wildfires more dangerous.

‘A perspective that sees natural vegetation only as potential fuel and dismisses ecosystem restoration targets as misguided, misses the point.’

In the immediate aftermath of the wildfires in Moray, gamekeepers called on government representatives to visit the affected areas and ‘learn lessons before it’s too late.’ In fact, the new muirburn licensing scheme they oppose will still permit burning on deep peat (now defined as peat deeper than 0.4 m) if it can be justified for restoring the natural environment, preventing wildfires or furthering research. How such justifications will be assessed remains unclear, but these exemptions may explain why so much effort is currently being made to emphasise muirburn’s potential use in tackling wildfire risk.

Pinewoods can be vulnerable to wildfire, especially in the stages before they reach maturity – but that shouldn’t mean we should abandon woodland regeneration.

Thinking outside the matchbox

A perspective that sees natural vegetation only as potential fuel, and dismisses ecosystem restoration targets as misguided, misses the point. In the end, the idea that continually burning the land is the only way to reduce the risk of wildfire is overly simplistic. There may be times and places where muirburn remains a useful tool, but its negative impacts should not be ignored.

It is wholly right that the new legislation seeks to address these negative impacts. From next year, the end of the muirburn season will be brought forward to the 31 March, offering greater protection to birds nesting earlier in our changing climate. As noted by Scotland’s Rural College: ‘adhering to the new rules will help ensure that the benefits (of muirburn) outweigh the problems.’

Fire risk or natural nursery? Juniper supports a wealth of wildlife but is also flammable. It is heavily suppressed by muirburn but grows well at rewilding sites.

Ultimately, Scotland cannot abandon its ambitions for restoring ecosystems simply because the resulting changes may, in some areas, bring a short-term increase in wildfire risk. The ‘rank’ heather and flammable scrub disparaged by some are, in fact, essential wildlife habitats, home to pollinators and rare species like the hen harrier. Rather than retreating from restoration, we must step up our efforts to prevent wildfires – by rewetting perilously dry moorlands, expanding naturally fire resistant habitats, and cracking down on avoidable ignition sources like campfires, carelessly discarded cigarettes and bottles, and disposable barbecues.

More than 95% of wildfires in Europe are directly or indirectly caused by human activities, reminding us that the simplest way to prevent wildfires is not to start fires in the first place. But if some wildfires are inevitable, there’s more than one way to reduce the threat they pose. An increasingly holistic approach to landscape planning is now being adopted in many European countries, integrating the restoration of naturally fire-resistant habitats with traditional tools such as prescribed burns. This approach is helping to build resilience and deliver a win-win for biodiversity and ecosystem services. Rather than depend solely on muirburn to manage wildfire risk, Scotland should develop a similarly holistic approach.